Notes on Designing Data-Intensive Applications

December 2024

Introduction

These are my notes on Martin Kleppmann's classic book "Designing Data-Intensive Applications". They are not meant to be comprehensive, but instead intended as a refresher for someone who has read the book before. No tokens were harmed in the making of these notes.

Chapter 2: Data Models

Relational Model vs. Document Model

Most programming languages use an object-oriented approach. MySQL doesn't neatly fit into that paradigm, even with Object-Relational Mappers (ORMs). This leads to interface mismatches. Storing JSON in a SQL column is possible, but such content is not easily queryable.

Document-Oriented DBs

Examples: MongoDB, CouchDB, RethinkDB.

- Schema is often enforced only in application code ('schema-on-read').

- Have better locality (i.e., no need to query multiple tables to fetch all details for an entity like a student's name, DOB, grades).

- Harder to do joins.

- If you denormalize data, it will be harder to keep the data consistent.

- Good for one-to-many relationships (e.g., easy to load an entire tree of documents at once, or index into a particular document).

- On a write, the entire document is usually rewritten.

Relational DBs

- Can more efficiently store many-to-one/many-to-many relationships with normalization (e.g., in a LinkedIn-like application, store info about a certain company once, instead of per-person).

- Require schema migrations for structural changes.

- Some systems providing locality, like Google Bigtable or Apache Cassandra (inspired from Bigtable), store data in rows distributed across multiple nodes. Each row has a 'partition key' to determine node placement in a distributed cluster.

Graph-Based Data Models

Property Graphs

Examples: Neo4j, Titan (now JanusGraph), InfiniteGraph.

- Each vertex consists of: a unique ID, incoming and outgoing edges, and a set of key-value pairs (properties).

- Each edge has a label describing the relationship between both vertices, and can also have properties.

- Easy to make queries that involve traversing a variable number of edges.

Triple-Store Databases

- Data is stored as (subject, predicate, object) triples.

- For example, (Lucy, age, 33) where 'Lucy' is the subject, 'age' is the predicate, and '33' is the object.

- Another example: (Lucy, marriedTo, Alain) where 'Lucy' is the subject, 'marriedTo' is the predicate, and 'Alain' is the object.

Chapter 3: Data Storage and Retrieval

Simple DB Storage

- Append entries to a file on disk.

- Hash the entry to form a key. Store a map from hash to the entry's index in memory.

- Writes are added to the end of the file.

- If the file gets too large, perform compaction.

SSTables and LSM-Trees

Slightly more complicated DB storage:

- New updates are written to an in-memory sorted key-value map.

- Once full, the in-memory map is flushed to disk as an SSTable (segment).

- There may be multiple SSTables on disk, with values in more recent SSTables overriding older ones.

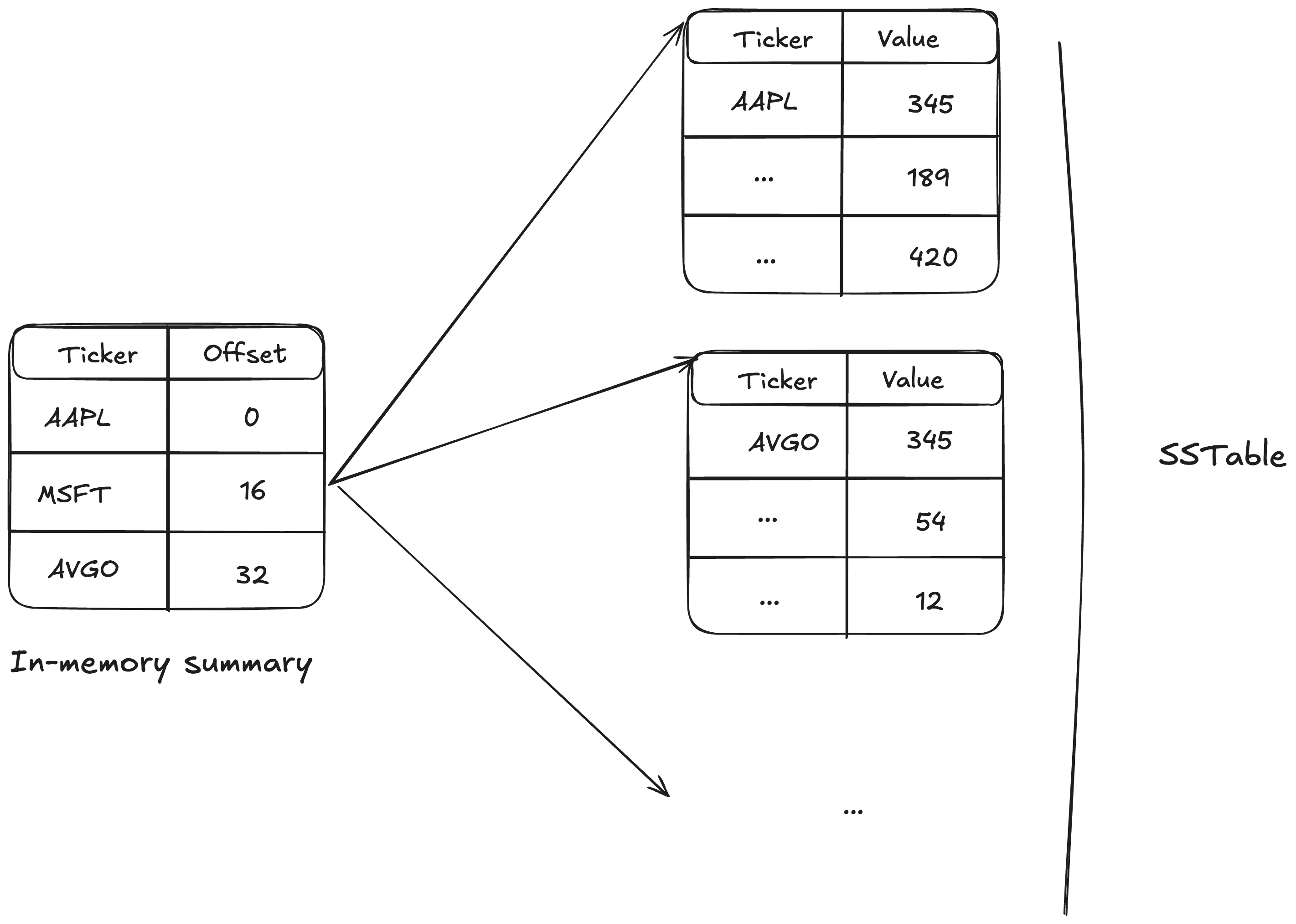

- Retrieval: First, look in the in-memory map.

- Second, look in the most recent SSTable.

- No need to iterate through whole table. Get the index to start searching from by using an in-memory summary, which stores the offsets for some key-value pairs.

- Segments are merged in the background (similar to merge sort).

- Used in RocksDB, LevelDB, Cassandra, BigTable.

Lucene/ElasticSearch also use SSTable-like structures to map a key (search term) to values (list of file IDs with that term). These are often used with Bloom filters and can be more efficient if you often search for keys that don't exist in the DB, as the in-memory hashmap method would incur unnecessary reads.

B-Trees

The most common indexing structure:

- Hierarchical tree with many children per node.

- Keys are stored in sorted order in the leaf nodes.

- Unlike SSTables, key-values are stored in fixed-size pages on disk.

- Since memory addresses are known, the end of one page can point to the start of another.

- Provides $O\log n$ access.

- Often used with a write-ahead log (WAL) for reliability if the B-tree on disk crashes.

A 'Clustered Index' means the row data is stored directly within the index itself, rather than in a different location.

OLTP vs. OLAP

- Online Transaction Processing (OLTP): Look at a small number of records, and update or insert some records.

- Online Analytical Processing (OLAP) / Data Analytics: Scan a large number of records and look at a few columns per record. Return some aggregate stats.

- To avoid interrupting OLTP with OLAP queries, data can be copied into a separate data warehouse periodically. This process is known as Extract-Transform-Load (ETL).

- Examples of systems used for OLAP/data warehousing: AWS Redshift, and SQL-on-Hadoop systems like Apache Hive or Spark SQL.

Column-Oriented Storage

- OLTP DBs usually store an entire record (row) together.

- For OLAP purposes, queries often access only a few columns at once (no need for `SELECT *`).

- Store each column's data together.

- This lends itself well to compression.

- Note: Cassandra and BigTable are still mostly row-oriented (they store all columns of a row within a column family together), though they offer flexibility.

- Writes are more difficult in pure column stores: potentially needing to write to many separate column files for a single record.

Materialized Aggregates

- These are pre-computed values for a set of data. For instance, sales per product regardless of date, or sales per date regardless of product.

- Usually involves reducing a dimension or more (by summing/averaging over that dimension).

Chapter 4: Encoding and Evolution

Evolvability refers to how a system can adapt to change (e.g., schema changes).

Common Encoding Formats

Random facts about JSON, XML, CSV

- XML and CSV cannot distinguish between numbers and strings representing numbers without ambiguity.

- JSON cannot easily distinguish between integers and floating-point numbers and has no native binary type (binary data needs to be text-encoded, e.g., using base64). JSON does handle Unicode in strings well.

Language-Specific Formats

- E.g., Python's `pickle`.

- These are often not well-versioned for schema evolution.

- Typically locked into a single programming language.

Protocol Buffers (and Apache Thrift)

- Each field is stored roughly as: 'type' + 'field number' + 'length' + 'data'.

- Field names are not stored in the encoded data.

- Forward compatibility: A parser encountering an unknown field number (from newer code) can ignore it.

- Backward compatibility: When adding a new field, it cannot be marked as 'required' if old code is to read new data.

Apache Avro

- Messages have a predefined schema (often written in JSON), but the schema itself (field numbers or names) is not stored with every encoded record.

- It uses a writer's schema (used to encode the data) and a reader's schema (used to decode the data).

- The reader's schema can specify how to fill in missing default values if fields are absent, or match field names with the writer's schema if the order of fields has changed.

- Avro schemas can be easily generated from database schemas.

Chapter 5: Replication

A common paradigm is to write to a leader and read from followers. Writes need to be replicated to readers.

- Synchronous replication: Propagate writes to all followers before confirming the write. This is often impracticable due to latency.

- Eventual consistency: Reads from read replicas will eventually reflect all writes.

- Monotonic reads: If a user makes several reads in sequential order, they will never read older data after having read newer data. For instance, After writes $x \rightarrow 0, x \rightarrow 1, x \rightarrow 2$, a user querying $x$ would never see the sequence $2, 1$.

- Consistent Prefix Reads: If a sequence of writes happens in a particular order, anyone reading those writes will see them appear in the same order. (e.g., If write $y \rightarrow 2$ depends on write $x \rightarrow 0$, a user must see $y \rightarrow 2$ only after having seen $x \rightarrow 0$).

- Difference between the two: Consistent prefix reads implies that a user always sees the DB as a snapshot of 'master' at some point in time, i.e. all writes and reads are ordered. With monotonic reads, a user might see a mix of old and new data. For example, suppose the live score of a soccer game is 2-3, with the away side taking a lead from 2-2. With monotonic reads, a user could see the score 1-3, which never happened, if they read the home and away scores separately.

Multi-Leader Setups

These are less common and more difficult to work with.

- Challenges include how to handle concurrent writes.

- Can be useful for scenarios like handling offline writes.

- Examples include CouchDB and Tungsten Replicator for MySQL.

Leaderless Setups

Examples: DynamoDB, Riak, Cassandra.

- Writes can be sent to several nodes, and read requests are also sent to several nodes in parallel.

- Version numbers can be used to determine which value is newer.

- Getting a failed node back online:

- Read repair: When a read detects stale data on one node (compared to others, using version numbers), the stale node is updated.

- Background `anti-entropy` process: Continuously copies data between replicas to ensure consistency.

- Quorum for reads/writes: The number of nodes to make requests against when reading ($r$) and writing ($w$) should satisfy $w + r \gt n$ (where $n$ is the total number of replicas).

- This aims to guarantee that at least one node read contains the latest up-to-date value (pigeonhole principle).

- In practice, it's not an absolute guarantee due to concurrent writes, or if writes fail on some nodes without meeting the quorum $w$ (failed writes might be undone).

- Usually provides eventual consistency.

- Quorum does not inherently fix concurrent writes of the same key with different values to different nodes.

- To handle concurrent writes:

- Attach a timestamp to each write and use 'last write wins' (LWW) in each node; older values get silently discarded.

- Use unique keys (e.g., UUIDs) for each write operation.

Version Vectors

- Use a version number per key per replica.

- The collection of all version numbers for a given key across all replicas is called a version vector. This helps detect and reconcile concurrent updates.

Chapter 6: Partitioning

Data can be split into different partitions (or shards) by key, usually computed with a hash function (e.g., MD5).

- This approach is not efficient for range queries, as such queries might have to be sent to all partitions.

- A compound key can be used, like in Cassandra:

- The first part of the key is often a hash (e.g., user ID) to distribute data.

- Subsequent parts of the key can be used for sorting within a partition (e.g., by timestamp for social media posts by a user).

Secondary Indexes

- With partitioned data, secondary indexes will often have to be maintained per partition (a local index).

- Alternatively, a global index can be used, but this index itself might be partitioned and stored across different partitions (a term-partitioned index).

- Reads from a term-partitioned index can be fast, potentially only needing to read from a single partition of the index.

- Writes can be slow, as inserting a single document might require updating secondary indexes across different partitions.

Rebalancing Partitions

Rebalancing is necessary when adding or removing nodes from the database cluster.

- How not to do it: Simply using

hash(key) mod N, where $N$ is the number of nodes. If $N$ changes, almost all keys would have to be moved. - A better approach: Create many more partitions than there are nodes and assign multiple partitions to each node. When a node is added or removed, only some partitions need to be moved.

- Examples: Elasticsearch, Couchbase, Riak use this strategy.

- HBase uses dynamic partitioning: a partition is split into two if it grows too large.

Locating Partitions (Partition Assignment)

How does the system know which node holds which partition?

- Using a coordination service for Service Discovery, e.g., ZooKeeper, which maintains the mapping of partitions to nodes.

- Using a Gossip Protocol: A client can send a request to any node, and that node can forward the request to the appropriate node based on its knowledge of the cluster state, which is spread via gossip messages.

Chapter 7: Transactions

Transactions generally aim to provide ACID guarantees:

- Atomicity: If some changes in a transaction fail, all changes are aborted. The transaction is all or nothing.

- Consistency: This often refers to an application-level guarantee that the database remains in a valid state according to defined rules (e.g., in a banking system, withdrawals should not result in a negative balance if not allowed). The database enforces constraints to support this.

- Isolation: Ensures that concurrently executing transactions do not interfere with each other. The highest level is serializability, where the end result of concurrent transactions is the same as if they had executed one after another, in some serial order.

- Durability: Once a transaction is committed, the data is not lost, even in the event of system failures (e.g., power outages, crashes).

Isolation Levels

Read Committed

- Only allows reading data that has been committed.

- Prevents "dirty writes" by only allowing overwriting data that has been committed (typically by acquiring a lock on an object when writing to it and holding the lock until the transaction finishes).

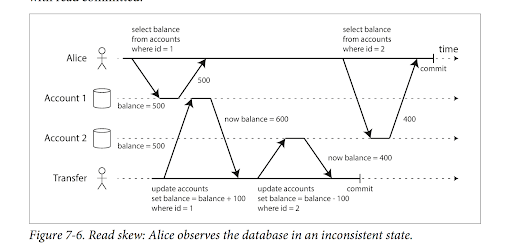

- Problem (Non-Repeatable Read): If a transaction reads the same data multiple times, it might see different values if another transaction commits changes in between those reads. For example, Alice reads account balances (e.g., $500$ and $400$), but reading the same balances again later in the same transaction might show different results if other transactions have modified them.

Snapshot Isolation / Repeatable Read

- All reads within a transaction are made from a consistent snapshot of the database as it was at the start of the transaction.

- A database often maintains multiple committed historical versions of an object (Multi-Version Concurrency Control - MVCC) if in-progress transactions are writing to the object. Each version can correspond to a snapshot for a transaction.

- Problem (Lost Updates/Write Skew): With two concurrent transactions that read some state and then write, one write could clobber the other if not handled carefully, or they could make decisions based on a stale premise (write skew).

- May require explicit locking at the application level or the use of atomic "compare-and-set" operations.

Serializable

- The highest isolation level. When two concurrent transactions execute, the end result is the same as if one transaction had run entirely after the other.

- Implementation methods:

- Actually executing transactions in a single thread (e.g., Redis).

- Two-Phase Locking (2PL) (distinct from two-phase commit):

- Transactions acquire shared locks when reading and can upgrade to exclusive locks if writing.

- Phase 1: Acquiring locks. Phase 2: Releasing all locks at once when the transaction commits or aborts.

- Deadlocks can happen; the system usually aborts one transaction and retries it.

- Index-range locking (often used with 2PL): Lock a whole range of objects to prevent phantoms (e.g., locking all doctor shifts or meeting rooms between 1 PM and 3 PM).

- Optimistic Concurrency Control: Allows transactions to proceed based on a snapshot of the database. Before committing, the system checks if any conflicts occurred (e.g., if data read by the transaction has been modified by another transaction). If conflicts occur, the transaction is typically aborted.

- Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI): An optimistic concurrency control method that detects and aborts transactions that could lead to serialization violations.

Write Skew

A type of anomaly that can occur even with snapshot isolation if not careful. Example: Doctors on call.

- Two transactions might independently read the number of doctors on call in a given time period.

- Both see a sufficient number (e.g., 2 doctors) and decide it's okay to remove one doctor each from their respective on-call shifts.

- If both transactions commit, there might be zero doctors on call, an outcome that would not have happened if the transactions had run serially (the second transaction would have seen only 1 doctor after the first committed).

- Solutions:

- Materialize Conflict: Explicitly create a resource that represents the condition being checked (e.g., a table 'number_of_doctors_on_call_per_period') and acquire a lock on the relevant entry in this table at the start of the transaction.

- Add an integrity constraint or use database features that enforce serializability for such operations.

Chapter 8: Problems with Distributed Systems

Networks can break or be split (network partitions). Requests may never be sent, or they might be sent with an unbounded delay. There may be no way for a sender to know whether a request was successful or not (e.g., did the remote node crash, or is the network just slow?).

Time in Distributed Systems

Each node in a distributed system may have its own clock, leading to discrepancies.

- Time-of-day clocks: What we conventionally think of as time (e.g., wall-clock time).

- These can be synchronized with a reference like NTP (Network Time Protocol).

- However, they can jump forwards or backwards (e.g., due to NTP corrections or manual adjustments), making them unsuitable for measuring precise elapsed time or ordering events reliably across nodes.

- Monotonic clock: Guarantees to always move forward.

- Can be used to measure elapsed time on a single node.

- NTP might speed it up or slow it down to align with true time, but it will not jump backwards. However, the absolute value of a monotonic clock is not comparable across different nodes.

Last Write Wins (LWW) conflict resolution: If timestamps (often from time-of-day clocks) differ significantly between nodes, or if clocks are not perfectly synchronized, LWW can cause later writes (in real time) to be incorrectly discarded if they carry an "earlier" timestamp, even when those writes causally depend on the ones they appear to precede.

Snapshot Isolation in Distributed Systems: Maintaining monotonically increasing transaction IDs (needed for consistent snapshots) is difficult in a distributed system without coordination. Google's Spanner database, for example, uses synchronized physical clock times (TrueTime API) as transaction IDs/timestamps, which requires careful clock synchronization.

RTOS (Real-Time Operating Systems): Used when the time needed to perform certain tasks needs to be deterministic and predictable. These systems often have no garbage collection (GC) pauses, and sometimes no dynamic memory allocation or GC at all, to ensure timely responses.

Identifying a Leader Node

- A common approach is to have a potential leader acquire a lease or lock, often associated with a fencing token (an auto-incrementing number).

- This lock typically has a timeout. The leader must renew the lease before it expires.

- Even if a leader node freezes for a while (e.g., due to a long GC pause) and then tries to issue writes after its lease has expired and another node has become leader, the storage system can reject its outdated writes by checking the fencing token. The new leader will have a higher token.

Byzantine Generals Problem: This refers to the challenge of reaching a consensus (e.g., agreeing on a leader or a committed value) in a distributed system where individual nodes may fail arbitrarily, including by sending malicious or conflicting information (e.g., using a wrong fencing token or lying about their state).

Properties of Distributed Algorithms

- Safety: A property that asserts that something bad will never happen (e.g., a committed transaction will not be undone, an invalid state will not be reached). Safety properties must always hold.

- Liveness: A property that asserts that something good will eventually happen (e.g., a request will eventually be processed, a leader will eventually be elected). Liveness properties may not hold at every single point in time but are expected to be satisfied in the future.

Chapter 9: Consistency and Consensus

Linearizability

Linearizability makes a distributed system appear as if there is only one copy of the data. Any value read is the most recent, up-to-date value and must be the same across different queries made at the same time.

This is different from serializability. Serializability concerns transactions in a database (the 'I' in ACID). A set of transactions are serializable if they can be arranged in a way that is equivalent to some serial execution. This order doesn't necessarily need to line up with when the transactions actually happened in real time. Linearizability is a stronger guarantee about recency.

What systems may or may not be linearizable?

- Single-leader replication: Can be linearizable, but not if using snapshot isolation from followers, or if a disconnected leader (believing it's still the leader) continues to serve requests.

- Consensus Algorithms (e.g., ZooKeeper, etcd): These are designed to provide linearizable operations.

- Multi-leader setups: Generally not linearizable, as different nodes may receive different writes concurrently, requiring conflict resolution later, which means reads might not see the absolute latest write.

- Leaderless replication: Not easily linearizable. Even if writes and reads are made with a quorum (e.g., $w + r > n$), concurrent operations or network delays mean a majority of nodes read from might still have outdated values if a write happens around the same time as a read.

CAP Theorem

The CAP theorem states that a distributed data store can only provide two of the following three guarantees: Consistency (often referring to linearizability in this context), Availability, and Partition tolerance.

- If a system prioritizes linearizability (Consistency) and is partition tolerant, then during a network partition (split brain, or when some nodes are disconnected), it may have to sacrifice Availability (i.e., cannot process some or all writes, or even reads, to ensure consistency).

- Conversely, if it prioritizes availability during a partition, it might not be able to guarantee linearizability.

Total Order vs. Causal Order

Linearizability implies a total order of operations. It's as if there's a single copy of the data, and every operation is atomic, so we can always definitively say which operation happened before another.

This is in contrast to a partial order, such as causal order, where some operations may be concurrent and thus incomparable in terms of their absolute ordering, but operations that are causally related (one depends on the other) are ordered correctly.

Causal ordering could be a property of a system that also implements total ordering (e.g., a replication log for a database with a monotonically increasing Log Sequence Number (LSN) enforces a total order, and this total order respects causality).

In the case of multiple nodes trying to establish a total ordering for operations:

- Naive approaches like one node using even numbers for IDs and another using odd numbers, or using a wall clock at sufficiently high resolution, do not inherently guarantee causal ordering (e.g., if the "odd" node's operations lag significantly behind the "even" node's operations but are causally dependent on them, the simple numbering might violate causality if not careful).

Lamport Timestamps

Lamport timestamps are a way to achieve causal ordering.

- Every operation is assigned a timestamp, typically a pair: (counter, Node ID). The counter is incremented by the node before an event.

- When a node sends a message, it includes its current Lamport timestamp. When a node receives a message, it updates its own counter to $\max(local counter, received counter) + 1$.

- This ensures that if event B depends on event A (A happens before B), then the Lamport timestamp of B will be greater than the Lamport timestamp of A.

However, Lamport timestamps alone are not sufficient for tasks like ensuring unique username creation across a distributed system - for uniqueness, a node still needs to communicate with all other nodes to see if a username is taken, effectively establishing a total order for username registration events. This can be slow.

Total Order Broadcast / Atomic Broadcast

Total order broadcast (also known as atomic broadcast) is a stronger guarantee:

- Reliable delivery: If a message is delivered to one node, it is eventually delivered to all correct nodes.

- Total order: All nodes deliver messages in the same order.

Examples of systems providing this include ZooKeeper and etcd. It is useful for:

- Database replication among nodes.

- Implementing distributed locks and fencing tokens.

- Building serializable/linearizable storage.

Conversely, linearizable storage can be used to implement total order broadcast (e.g., by sending a sequence of messages, each written to a linearizable register to get an incrementing sequence number).

To create a linearizable incrementing integer (often needed for total order broadcast or sequencing), a consensus algorithm is typically required to confirm the integer's value across multiple nodes.

Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

2PC is an algorithm used to achieve atomic transaction commit across multiple nodes (a form of consensus on whether to commit or abort).

- On a single node, atomicity can be achieved using a write-ahead log (WAL) alongside disk storage.

- With multiple nodes, all participating nodes need to agree on committing or rolling back.

- Phase 1 (Prepare): The coordinator sends a "prepare to commit" message to all participants. Participants respond "yes" if they are ready and promise to commit if told to do so (they log necessary info to disk to survive crashes), or "no" if they cannot commit.

- Phase 2 (Commit/Abort):

- If all participants vote "yes", the coordinator decides to commit, writes a commit message to its own log, and then broadcasts the commit message to all participants. Participants then commit.

- If any participant votes "no" or fails to respond, the coordinator decides to abort and sends an abort message to all participants.

- The coordinator will keep retrying to send the commit/abort message until all nodes acknowledge. Once a participant has promised to commit, it cannot unilaterally undo its decision.

- 2PC generally has performance issues, especially if the coordinator fails.

- An example application is XA transactions (e.g., for distributed transactions involving two different database systems).

Other Consensus Algorithms (e.g., Paxos, Raft)

Algorithms like Paxos and Raft are also used for achieving consensus and implementing total order broadcast. They usually involve two main phases or aspects:

- Leader election.

- The elected leader then proposes new values, and a protocol ensures that nodes agree on these proposed values in order.

ZooKeeper is an example of a system that uses a consensus algorithm (Zab, which is similar to Paxos). It provides a distributed key-value store that other distributed systems often rely on. It uses total order broadcast to ensure the same sequence of writes on all nodes. It's also used for service discovery, though consensus algorithms might be overkill for simple forms of service discovery.

In summary: Consensus algorithms $\rightarrow$ Total Order Broadcast $\rightarrow$ Linearizable storage across multiple nodes.

Chapter 10: Batch Processing

MapReduce (Hadoop, Pig, Hive)

MapReduce is a programming model for processing large datasets in parallel on a distributed cluster.

- Reads input from a distributed filesystem (in Hadoop: HDFS), where file blocks are replicated on multiple machines to tolerate disk or network failures.

- The process generally involves:

- Reading records from the filesystem.

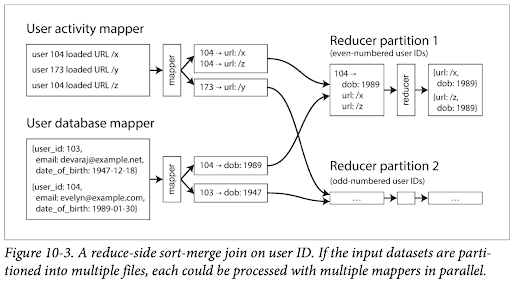

- A Mapper function: Called once for every input record. For each input, it outputs zero or more key-value pairs. These pairs are typically stored on the mapper's local disk.

- A Reducer function: After the map phase, data is shuffled and sorted by key. The reducer gets all values associated with a single key (key $\rightarrow$ list of values) and produces output records.

- Often, multiple MapReduce jobs are chained together to perform complex processing.

- Commonly used for tasks like sort-merge joins (See illustration above). The alternative, like querying a user database for each activity entry separately in a large log, would be too slow.

- Skew: Certain "hot keys" (keys with many more values than others) may lead to skewing the processing load towards certain reducers. Some systems allow techniques like duplicating the data for a hot key over several reducers to distribute the load.

- It is also possible to have map-side only tasks/joins, e.g., if one of the datasets being joined is small enough to be held entirely in memory in each of the map tasks.

- Output data from reducers can be written as a brand new database or key-value store file.

- MapReduce is less suited for tasks that require the process to be run multiple times iteratively until a condition is met (e.g., until a graph is fully traversed, though iterative versions exist).

Comparison with MPP Databases

- Massively Parallel Processing (MPP) databases typically require querying with SQL and store data in a structured format.

- MapReduce, on the other hand, can more easily read and process unstructured or semi-structured data.

Materialization in MapReduce

- In MapReduce, the intermediate state between the mapper and reducer (the output of mappers) is typically materialized (written to disk).

- This contrasts with the Unix philosophy, where the output of one command is often piped (streamed) directly to the input of the next, with only a small in-memory buffer.

- Reducers generally have to wait for all mappers to finish before they can start processing all their input.

Dataflow Engines (e.g., Spark, Tez)

More generalized frameworks than traditional MapReduce:

- Functions need not be strictly map or reduce tasks; more complex data flow graphs (DAGs) can be defined.

- There's no strict requirement to sort outputs from map-like stages before reduce-like stages if the logic doesn't need it.

- All joins and data dependencies are specified, so the system can be smarter about scheduling tasks and allocating machines.

- Intermediate state can often be stored in memory rather than always written to disk, improving performance.

- A later operator in the dataflow graph need not always wait for an earlier operator to be entirely finished processing all its data.

Graph Processing (e.g., Pregel, Apache Giraph)

Specialized systems for large-scale graph processing:

- Processing often occurs in iterations (supersteps).

- In each iteration, each vertex can process input messages sent to it from other vertices in the previous iteration, update its state, and send messages to other vertices for the next iteration.

- Typically, a vertex only processes new messages relevant to it, not necessarily all graph data in each iteration.

Chapter 11: Stream Processing

Publish/Subscribe Systems

Systems for handling continuous streams of data (events).

- Some systems go straight from producer to consumer:

- Often via UDP or TCP, e.g., for financial data feeds.

- This requires the application to monitor for dropped messages and handle reordering.

- Others use a message broker/queue (an intermediary):

- Acts like a server (or cluster) and a database, to which producers send messages and from which consumers retrieve messages.

- Examples: RabbitMQ, ActiveMQ, Google Cloud Pub/Sub.

- Fan-out: A message can be sent to multiple consumers (e.g., for different types of processing), or each message can be sent to just one consumer from a group (e.g., for load balancing work).

- Messages may be re-ordered by the broker or network, depending on the system and configuration.

Log-Based Message Queues

- Many traditional pub/sub systems store only a small buffer of messages. A new consumer, or one that has been offline, might not be able to read old messages.

- Alternatively, an append-only log (similar to commit logs in databases) can be used as the basis for a message queue. The log can also be partitioned by topic.

- Examples: Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis Streams.

- The log is typically divided into segments, and older segments may eventually be archived or deleted based on retention policies.

- This model makes it easier to re-run consumers from older offsets in the log (e.g., to reprocess data or recover from errors).

Event Streams and Databases

Ideas from event streams can be applied to databases, and vice-versa.

- An event log is conceptually similar to a replication log in a database.

- Change Data Capture (CDC): The process of capturing all data changes made to a source database so that they can be streamed to other systems (like an analytics pipeline, a search index, caches, etc.).

- The search index, in this case, is a derived data system from the primary database via its change log.

- For example, Facebook's Wormhole.

- Log compaction can be used to shorten the log by keeping only the latest value for each key, discarding older updates for the same key (e.g., in Apache Kafka).

- Downside: Reader nodes (derived data systems) may be out of date with the primary event log, since updates are typically asynchronous.

Processing Streams

Stream processing often involves transforming one or more input streams to create other output streams or update state.

- Processing based on time (windowing):

- Events in a stream often have timestamps. Processing might involve grouping events by time windows (e.g., calculating aggregates over 5-minute intervals).

- Not all messages for a specific time range (say, 3:55 PM to 4:00 PM) will arrive at the processor at exactly 4:00 PM due to network delays and clock skew. These are "stragglers."

- Strategies for handling windows and stragglers:

- Process whatever arrives within a certain period (e.g., process events for the 3:55-4:00 PM window until 4:05 PM), and ignore or specially handle stragglers arriving later. Alarm if the percentage of stragglers rises significantly.

- Publish a correction or updated result later when straggler data is processed.

- Stream processing can involve joins with other streams or with static/slowly-changing tables.

Fault Tolerance in Stream Processing

- Micro-batching (e.g., processing data in small, discrete batches of 1 minute) or checkpointing (periodically saving the state of the stream processor) allows replaying a batch or restarting from a checkpoint if a failure occurs midway. However, any side-effects (e.g., external API calls) from the partially completed batch might happen twice if not handled carefully.

- Two-phase atomic commits can be used for stronger exactly-once processing guarantees when interacting with external transactional systems, but they are complex and can impact performance.

- Making processing idempotent: Design operations so that applying them multiple times has the same effect as applying them once. For example, include a unique ID with each message or event; the consumer can then track processed IDs and ignore duplicates.